- Home

- Jerome Stueart

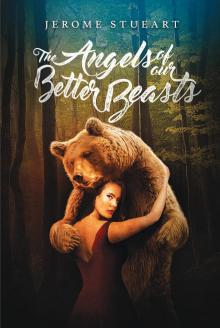

The Angels of Our Better Beasts

The Angels of Our Better Beasts Read online

FIRST EDITION

The Angels of Our Better Beasts © 2016 by Jerome Stueart

Cover artwork © 2016 by Erik Mohr

Cover design © 2016 by Samantha Beiko

Interior design © 2016 by Jared Shapiro

All Rights Reserved.

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either a product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Distributed in Canada by

Publishers Group Canada

76 Stafford Street, Unit 300

Toronto, Ontario, M6J 2S1

Toll Free: 800-747-8147

e-mail: [email protected]

Distributed in the U.S. by

Consortium Book Sales & Distribution

34 Thirteenth Avenue, NE, Suite 101

Minneapolis, MN 55413

Phone: (612) 746-2600

e-mail: [email protected]

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Stueart, J. (Jerome), author

The angels of our better beasts / Jerome Stueart.

Short stories.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-77148-407-7 (paperback).--ISBN 978-1-77148-408-4 (pdf)

I. Title.

PS8637.T865A8 2016 C813’.6 C2016-904209-X

C2016-904210-3

CHIZINE PUBLICATIONS

Peterborough, Canada

www.chizinepub.com

[email protected]

Edited by Andrew Wilmot

Proofread by Ben Kinzett

We acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts which last year invested $20.1 million in writing and publishing throughout Canada.

Published with the generous assistance of the Ontario Arts Council.

I think I could turn and live with the animals,

they are so placid and self-contained;

I stand and look at them long and long.

They do not sweat and whine about their condition,

They do not lie awake in the dark and weep for their sins

—Walt Whitman

Table of Contents

Sam McGee Argues with His Box of Authentic Ashes / 9

Lemmings in the Third Year / 15

Heartbreak, Gospel, Shotgun, Fiddler, Werewolf, Chorus: Bluegrass / 33

Old Lions / 73

The Moon Over Tokyo Through Fall Leaves / 77

How Magnificent is the Universal Donor / 93

Bondsmen / 111

Et Tu Bruté / 123

Why the Poets Were Banned from the City / 127

You Will Draw This Life Out To Its End / 137

For a Look at New Worlds / 175

Brazos / 187

Awake, Gryphon! / 197

Bear With Me / 211

The Song of Sasquatch / 229

Sam McGee Argues with His Box of Authentic Ashes

It is rumoured that Sam McGee once ran into a young man selling the authentic ashes of Sam McGee, the cremated hero of “The Cremation of Sam McGee,” by Yukon poet Robert W. Service. Amused, he bought them, because how many men could say they bought their own ashes?

I was offered the chance to buy a piece of myself

the other day, and so I did. I came in a small bag,

which I found very saddening and undignified,

so I bought myself a nice hand-carved wooden box—

and I carefully sifted myself into it.

And I wondered, half in morbid amusement,

which part of myself I had purchased—the arms

of a road builder, the bad luck as a gold panner,

the sedate life of a married farmer, a churchgoer.

Was it the best parts of my life, or the worst?

I opened the box to examine myself up close—

to see what kind of man I was—the fine grain of me,

the coarseness, the smell of my life all burned up—

—when I was surprised to hear a voice come from the box—

like an excited street-corner barker. “What a treasure you hold

in your hand! What a great life you have purchased!

A lucky man is he who holds the ashes of Sam McGee!”

“Oh really,” I chuckled. “Tell me about Sam McGee,

this treasure.”

And, with a raucous, carnie shout, he quoted the poem—

the life story of Sam McGee, as written by Robert W. Service—

and unflattering, unmanly, untrue portrait of a Sam McGee

that never existed. It was just a name that Robert Service,

the damn Yukon poet, snatched up from the bank register

where he worked, needing a name to rhyme with Tennessee.

It was my name he snatched from that register I signed.

So I got to be the wimpy, whiny complainer, frozen solid

on a Christmas Day, stuffed into the boiler of a derelict

paddle wheeler, and brought back to life—briefly—in the heat

of the boiler fire. “Since I left Plumtree down in Tennessee,

it’s the first time I’ve been warm.”

“Stop!” I told the Ashes, as I had told every man, woman

and child I ever met, “That. Isn’t. Sam McGee!”

The Ashes, however, disagreed. “Why not?”

“Because for one thing, I’m Sam McGee—and I’m from Ontario.”

The Ashes drifted in thought for a moment. “Who wants to be Sam McGee from

Ontario? It doesn’t even rhyme.”

“It doesn’t matter if it rhymes; it’s the truth. I’m Sam McGee! I didn’t take a

mushing trip on Christmas Day! I never whimpered about the cold! I was never frozen solid! I was never stuffed in a boiler! I never came back to life!”

The Ashes said, “Well, what did you do?”

I was caught off guard, I’ll admit. Always defending

myself against the fame of the false Sam McGee, saying

who I wasn’t; what I didn’t do; what never happened to me.

I hadn’t really—practiced—my own biography. And I stuttered

some events I believed important in my own life, a beautiful,

settled, prosperous life with family and farm.

And the more I talked, the more I was tempted to embellish,

to make things rhyme—to swath a coat of brightly coloured paint

on the history of my life. But I didn’t. I was true to my life,

every mundane thing.

But the Ashes, the true barker of the living world,

asked me, “Wouldn’t you rather be Sam McGee from Tennessee?”

“No, I wouldn’t,” I said, and I was strong at first.

But the Ashes talked about immortality.

My name was on the tongues of bards across the world

and would be for hundreds of years. I was in the homes

of millions and millions of readers. I would be remembered

for a sort of Christmas Day resurrection,

the ability to withstand the fire,

to be renewed by it—

oh, the ashes got terribly metaphorical and metaphysical.

“No one knows of Sam McGee from Ontario—

and no one will. But you can choose to be

the Sam McGee of Robert W. Service and be

remembered

forever—and isn’t being remembered

more important than being true?”

I quivered, even shivered.

To have passed through this world making no mark

bigger than a few stories my children will remember—

compared to that of a life that entertained millions

in a story unlike any other—even untrue—

what would I do?

The Ashes, sensing victory, roared, “What has the truth

ever done for anyone? It’s really not that catchy.

What you need is a good story.”

“Story,” the box whispered, “is a light—

whether it shines on you or burns you up,

it’s still a light everyone can see.

And in this world of unnoticed billions,

there’s a light shining on you, Sam McGee.

Deny Ontario, and be from Tennessee!”

And I thought of my life, and I thought of my wife, and I looked at my ashen friend,

then “Here,” said I with a sudden cry, “is the way this story will end.”

I would be Sam McGee from Ontario,

but I would keep Sam McGee from Tennessee

on my bedside, dead, cremated, a reminder

that six billion people and their happiness was not

worth my name, a reminder that a good life didn’t have

to be one that was recited on a stage, that bliss

didn’t have to be shared like the morning news,

that I could allow Sam McGee from Tennessee

to rest in peace in a box forever. I didn’t have to compete

with Sam McGee—

I just had to ignore him.

But sometimes, at night, I can hear the Ashes whisper through the wooden lid.

In the dark, their voices say, “it’s not too late to become someone GREAT!”

But I turn over in bed and smile.

These ashes are nothing special. Ashes say that to everyone.

Lemmings in the Third Year

I’ve always preferred my rodentia frozen, tagged, weighed, and placed in plastic bags; it unnerves me now to be interviewed by them. The lemmings, four of them, carry notebooks and an inkwell that looks like a dark blue candelabrum. They have followed me out onto the tundra, unsure why I am here. Since it is their job to observe me and ask questions, they approach so they won’t miss the one vital piece of information for which they have been looking all along. But I’m not in a talkative mood.

The tundra is quiet. I would have expected that, really, back home in the real Ivvavik National Park, the real northern coast of the Yukon Territory. I would have expected the passive look of the Beaufort Sea as it gives in to blocky chunks of ice that grow in numbers like a scar forming on the water. I can still see the grass underneath a light snow. I expect that, too. The vastness of the Arctic is amazing, breathtaking, and all this you can read about in books, see on television specials, even visit.

“What are you thinking about, Kate?” one of them asks me, breaking the silence. They have scratchy, tiny voices—not like Alvin and the Chipmunks, but more like carnies operating a Ferris wheel for the sixth day in a row, people who smoke a lot. Lemmings chitter.

“I’m thinking about home,” I tell them. I open the videophone that David gave me before we left. It was working when we first crashed, but it’s not picking up a signal anymore. I am so roaming it’s pathetic. You can’t see it out there in the sky overlooking this flat, coastal plain, but there is a hole in midair that our plane came through, and it’s completely invisible. It’s only several hundred feet off the ground, we guess.

“Home is Las Vegas,” one of them says.

I laugh. “Yeah. You guys would fit in well there, especially in a casino, or maybe even your own show.” I wish I could mark the air with a dye—so I’d know where the window is. I pick up a stone and think about throwing stones up one after the other until one of them disappears, but that’s several hundred feet. Couldn’t make that if I tried. Besides, there’s a chance that any window we came through has closed or moved on. That we are here for a long time. Like the ice freezing up behind you—we may be here until a lead opens in the air to take us back home, away from this land of speaking wildlife.

“She wants to go home,” one of the females says. “She wants to give her research back to her people.”

The wind batters my blue parka and drives black hair back into my face.

“No one,” I laugh, “would believe our research right now. It wouldn’t make a difference to them.” They watch me punch the small buttons on the videophone. These phones are still so new; I don’t know how to operate it like David would.

“Research is factual. It has to be believed,” one of the males says.

“How can research be unbelievable?” a female asks.

I look up at the sky. From the sea to the mountains in the distance, it is all one flat colour.

“All right,” I say, and put away my phone. I take a big breath. This is going to be a tough one. “It’s time you learned about the scientific method.”

I hear them behind me, scratching something on notepads. Every once in a while, there is a glub sound of a paw dipping into the ink and coming out again.

>?

The day hadn’t started off well. I have lived in a cabin for the last few months with two other scientists and a pilot who was trying to fix our plane. Except he had no parts. Because—surprise!—there were no stores for aviation spare parts in this place.

Dr. Claude Brulé, the lead scientist on this expedition, had abandoned science altogether for theatre. I no longer saw him in the cabin, as he now stayed with a polar bear that lived farther inland. The polar bears here were decidedly friendly and had a non-aggression pact with most of the animals, except the seals, but even that depended on times when the seals were selling the bears something and when they were not.

The bears were putting on a play for us. Actually, they were putting on a play before we got here, but Dr. Brulé had been helping them with direction since last week. He’d always had a fondness, he said, for Shakespeare.

Dr. Kitashima and I live in the cabin together. He is full Japanese, but speaks English much better than I speak Japanese. My father never spoke much of his own language around us girls, so I didn’t pick up much. I did study Japanese in college a bit, but didn’t speak it well enough to impress a native of Japan. Dr. Kitashima doesn’t say so, but I know he’d rather I not speak any Japanese at all. He said I spoke it like a man.

Rather than abandon what we came here to do, Dr. Kitashima and I had been trying to conduct our experiments on this tundra. We had this belief—or I had, until today—that one day we would get back and that, in the meantime, science would be what would keep us sane. If we concentrated on our work, we would be able to think our way through this, figure out another way to get home. At least, he told me once, we would pass the time.

Our pilot, Ernest Stout, had a tent set up by the plane, but eventually, as winter set in, I knew that he would join us. His dog, River, had started to talk to him for the first time, and he didn’t know what to do.

It’s strange. I can’t explain how strange it is. We had watched movies all our lives with talking animals; I had read books when I was child—Watership Down, fairy tales, Charlotte’s Web—and none of them prepared us for all the animals talking. I haven’t heard a mosquito yet, but I’m willing to bet that they have some language, too. The only reason that the bears, lemmings, ungulates, walruses, and birds (for the most part) speak English is because the bears learned it first, and they taught it to everyone else.

They all speak with a south-western twang.

“Do you mind if we continue our questioning?” one of the males asked me. They clambered on top of one of the huge wooden desks inside this cabin, dragging with much effort, their inkwell. At one point I

had named them, but was so embarrassed about doing so that I refused to talk to them as individuals.

“I really have a lot to do,” I lied. What is there to do in a place you can’t escape? There were no research centres, no universities, no schools to get into, no professors to impress, no jobs to interview for. There were no other humans in this place that I’d seen, and the animals all acted as if we were the newest thing. For a while, we had many bird visitors—kittiwakes mostly—nosing around, wanting to know what kind of disturbance we would make to the environment.

I shuffled some papers on the desk, picked up my pen, and began writing a letter to my long-lost boyfriend David, whose worst nightmare had happened: he had lost me, just as he suspected he would.

He’d said, “If I let you go to the Arctic, do you promise to come back and get a degree here in Vegas?”

I couldn’t have told him yes. I never wanted anyone to control my decisions, box me in. Well, now I had the whole world to move in, free and unencumbered by any other person but one bear biologist, one botanist, and one pilot.

Dear David, I am doing fine. How are you? I wrote.

“Will you be eating us soon?” one of the lemmings asked.

I looked up. Two of them were poised to write, one was approaching my elbow, and the other was aside the inkwell, looking horrified.

“I’m not going to eat you,” I told them.

“But we’re highly nutritious,” one of them said.

“We have plenty of food.” I gestured over to the back room, which housed a huge supply of seal and some vegetables that the bears traded for. “I’m not the big enemy this time.”

“Do you enjoy eating lemmings?”

One of the females tapped his shoulder. “We know they do.”

“We’ve never said that,” I said.

“You enjoy meat?”

“I do eat meat, yes. But—”

“You will enjoy us. The bears like to dip us in gelled seal fat. I think that’s what I would like. I’ve heard it is very tasty.”

I shuddered. Researchers in the lemming community were basically sacrificial lambs. They came and did surveys to determine who would be their big predator in the fourth year, offering themselves as food after the data was delivered back to their community. All this data was compiled in the second and third year, and a major enemy was predicted. I’d never seen if this was effective; I’d heard from the bears it was not. According to them, the lemmings became paranoid by their own data and panicked in the third year, breeding like crazy to survive the coming “holocaust,” making the fourth year a feast for all predators. It was a terrible, cyclical event, but it happened. Lemmings on our side of the window had spurts in population as well. It had never been a crisis, as far as I know.

The Angels of Our Better Beasts

The Angels of Our Better Beasts