- Home

- Jerome Stueart

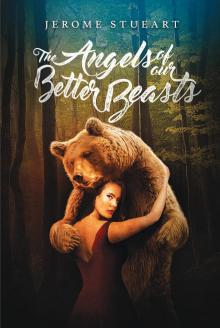

The Angels of Our Better Beasts Page 2

The Angels of Our Better Beasts Read online

Page 2

But then, I’m not a lemming.

“I want to be cooked on that beautiful blue flame,” one of the females said, pointing to our small gas hot plate, which we hadn’t used in a while since we were running out of fuel and wanted to conserve for the nine-month winter ahead.

“You can’t,” I said coldly. I waved the pen at them threateningly. “We aren’t going to use that very much anymore.”

“But I get a request,” she demanded.

“Sorry. I’m not even going to eat you. You might as well pick another subject to interview.”

They were undeterred. “Did you come here specifically for lemmings?” a male asked.

Dr. Kitashima came in the door, and I felt as if I were saved. “Doctor,” I said, “what have you heard?”

“Mr. Stout believes the landing gear is completely out of commission. Will not be able to fly the plane without it.” He took off a stocking cap and placed it on another desk. He then went to the removable panel in the floor and grabbed a rake leaning against the wall and started to rake the coals beneath the wood, nestled down a few inches into the ground. It was not the best heater, but it worked.

I’d already heard some of that news yesterday. But I didn’t want to believe it. I looked away, told myself that I could be as stoic and practical as the next scientist. I could make do with what we had, live a life here in the Arctic watching plays put on by bears, talking to doomed lemmings, shooing away nosy birds and foxes. I certainly didn’t want to be the weak and emotional one on this expedition—the one who couldn’t pull her weight. No reason to accuse me or fulfill their expectations.

“You have remained busy?” he asked.

“I’ve been working on reports,” I said, sticking the letter to David underneath another pile of papers. I hope he didn’t really listen to my voice—there was a catch in it. He smiled. “Good. That will pass the time.”

He is short like me, and his face looks like a windshield after it’s been broken. He seems much older than he actually is—I thought maybe fifty or so. Really no need for him to look as old as he does. Despite his sometimes annoying habit of treating me like his research assistant, I get along well with him.

“You have been talking to our friends,” he said, indicating the lemmings.

“I don’t really want to—” I started to say, but one of the lemmings interrupted.

“We are in the midst of an interview,” he reminded me. “Did you come here for lemmings?” he asked again.

I ignored them, getting up and moving to where Dr. Kitashima stood. I started telling him how these lemmings were driving me batty.

“Are you perhaps avoiding the question?” one of them asked. “We’ve had that happen before.” He turned to the others. “I would put, yes, she has come for lemmings.”

“You can’t put that!” I said. “I didn’t confirm.”

“You confirmed by your avoidance.”

“That’s not research,” I told them.

“We hypothesized that many subjects lie and avoid. This just proves our hypothesis is a true one.”

I blew up. “If all your data is skewed to answer your hypothesis, then why do research at all? Why not stay in your lab and make up whatever you want?”

They were quiet for a moment.

One of them said, “When data relies on the answers of individuals, isn’t there always a margin for error due to the unreliability of interviews?”

“If they are unreliable, why would you do them?”

“How else will we collect data?”

“Look, I don’t have all day to explain to you how research is done. But I’ll tell you this: there are other ways to calculate threat in a closed system besides interviews. What am I saying?”

Interviews—we’d never tried interviews before now. No one—no animal—could tell us what they were thinking. And, come to think of it, if they had been able to, we would have solved a lot of mysteries regarding how animals communicate, what they are thinking. What a boon to science! ’Course, that’s called anthropology.

I walked over to them. “Okay, what you are doing is more of a psychological survey. Now, that’s not my field. But I do know this: surveys have a large margin of error, and that error margin rises when you are dealing with personal questions. You are asking predators if they are planning to eat you. Now let’s think about this: Why would a predator tell you he was going to eat you?”

“They all tell us they will eat us.”

“So how do you determine which one is the most threatening in a given year?”

“We go by intuition—in the way that the predators answer the questions.”

“Intuition? That’s not scientific.”

“But it has been accurate for generations.”

“Wait. You’re telling me that the questions are a front—a disguise—for you to assess each predator through nonverbal cues?”

They conferred among themselves for a moment in lemming-speak—a high-pitched chittering. One of them looked up. “We cannot answer the question without skewing our results.”

I was ready to throw something. “You are a walking, talking, insult to science!”

Dr. Kitashima swept the floor around me, asking me to lift my feet one at a time. “Perhaps this is opportunity.”

“What opportunity?” I snapped.

“To spend time. Teach them about science. Real science. Help them see.”

He swept the cabin methodically, in rows, until the dust was in one pile, and then, without another word, swept the pile out the door.

>?

That’s why we are here now, the five of us, me and my team of protégés, approaching a snowy owl’s nest on our bellies. In the distance, a snowy owl sits. It’s a female, as they alone incubate the eggs. Males are usually out gathering food. This is about the distance that we need to be. She can probably see us, but that doesn’t matter because my point will still come through.

“All right, let’s stop here.”

“Why don’t we go up to her?” one of them says.

“We don’t want to alter the results of observation. A scientist has to keep objective distance at all times. She doesn’t want to influence the results of her research. Of course,” I pause to remove a small rock from underneath me, “there is a theory that every observer has an effect on the thing she is observing. The Hawthorne Effect.”

They scribble on a notepad and repeat, “Hawthorne Effect.”

“But we’re going to forget that,” I say. “We are going to maintain our distance. The first thing you have to learn is how to observe.” I look at the owl through my binoculars. She appears sedated.

“Okay, what is the owl doing?” I ask. “Observe her and tell me what you see.”

They watch for a few seconds. A female says, “She is looking for us.”

“What makes you say that?”

“She is looking straight at us.”

I glance through the binoculars, “No, actually she looks like she’s asleep.”

“She is faking,” they say.

“You don’t know that. You have to go by what you can see.”

“She is stalking us,” they say.

“No, you’re missing the point. You can’t make up things—you can’t interpret the data you don’t have. You have to look at what she’s doing and just write that down. Can we do that? Can you just write down what you see?”

They scribble for a few moments, looking up at the owl periodically, and then returning to scribbling. One of them even draws a nice picture of the owl.

“That’s very good. See, now this guy over here has drawn a sketch to go with his observations. That’s very cool, uh . . .” Suddenly I want to name them again. “Are you Luxor?” I ask.

“I’m Orleans,” he says. I’m embarrassed because I named them after casi

nos. I wasn’t feeling quite myself that day—a little excited, a little unprofessional. But now they were colleagues and not subjects, so it was different.

“Orleans, yeah. Okay, Orleans here has drawn a picture,” I say again.

“It’s a very nice picture,” Mirage says. “Should we all draw pictures?”

“Well, pictures are nice.” I prop myself up on an elbow. The wind whistles under my hood. “But not necessary. Just writing down notes of what you’re observing is the important part.”

Bellagio says, “She’s awake! I saw her move.”

“Good.” I turn back and look through my binoculars. “All right. Now, look at what she’s doing.”

“She’s cleaning herself,” Mirage says.

“She is,” I confirm. “Good, write that down.” They proceed to write down this information.

“Why is this important? It doesn’t tell us if she will eat us,” Luxor says.

“Animal behaviour is an indication of their patterns, their habits. If we know the routine of this owl, we can then predict behaviour.” I feel a bit like a professor instead of a graduate student.

“How long before we know if she will eat us?”

“Well, Mirage, you have to observe her over time. Like, a long time. Like, a really long time.”

“A couple of days?” asks Bellagio.

“Well, some of these can last for months or years. Depends on funding.”

“Funding?” they ask.

“Not important here,” I say. “We have to watch this owl and find out what she’s like, what she does, what her habits are. Habits don’t lie like statements about your habits can.”

“Like when we caught you lying,” Luxor says.

“I wasn’t lying,” I sigh. “Okay, it’s true, I came here to observe lemmings. I’m a biologist. I want to do this for a living. I was going to do just what we’re doing now.”

“Look at us through binoculars?” they ask.

“Yes, basically. Yes.”

“What’s basically?”

“That’s not important.”

“You would have snacked on us,” Bellagio says.

I look back at the owl, and she has something in her mouth. It’s a lemming.

“You guys better see this,” I say.

They hum in chorus and breathe in, and then a world of scratching on notebooks.

“Well, we’re done here,” they say.

“What?” I look back as they start to leave. Bellagio has the audacity to cross over my back. “Where are you going? You’re not done.”

“We observed her eating a lemming. That answers our question.” Luxor wipes his hands on his fur, smearing it with ink.

“You don’t know how often she does that,” I say to these science neophytes. “You don’t know if the lemming was days old.”

“But she was eating her. Clearly, she has the appetite and the habit.” Bellagio turns to go.

Mirage stops. “But we don’t know how often this owl does that, or if all the snowy owls follow her pattern. Kate is right. We have to stay and watch longer.”

Good job! I think.

Orleans and Luxor are off, crossing the tundra. “I have a better idea,” says Orleans, “we’ll just ask her.”

“That won’t give you real data!” I call out after them. My words get lost in the wind. “This is not part of the scientific method! Wait!” But they are heedless.

“Men,” I say.

“Males,” Mirage and Bellagio say, but they aren’t as upset as they need to be. They say it in a dreamy sense. “They always have such confidence.”

“Listen,” I tell them. “That’s an owl. What’s to stop her from eating them?”

Mirage titters. “Wouldn’t it be wonderful to be swooped up by an owl? Feel that rush of excitement, even as the talons surround you!” She clasps her little paws in front and her eyes go wide.

I underestimated their death wish.

I stand up, brush off my coat, and walk quickly to catch up with the two others in my team. Back home in Las Vegas, I was in charge of the Mendor Lab. Diane Mendor really ran it, but when she got engaged, she became wrapped up in a lot of other things, and I just naturally took over. This feels like the lab all over again: a bunch of young grad students who think they know what they’re doing, blustering right into a big pit. Live and learn.

Orleans and Luxor have scampered right up to the owl, but the owl is not reacting to them in the way I expect. She sees me, obviously, and this alarms her. Even though I’m shorter than the average human, there is no average here to work from, so I look tall. I’ve always wanted to be tall. Perhaps I stretch a little when we get up close to her. I’ve also only seen dead owls this close. I know a fellow student who’s going into zoo science. She visited a whole owl sanctuary in California. Said they scratched a lot, and they were flighty. I wonder what owls here are like.

This one has her feathers ruffled, but she’s not hissing. She’s not moved off the nest, either, but I can’t tell if she’s upset or excited to see us.

“Hello,” I say to her. “My name is Kate.”

“Well, these are nice. Thank you very much, Kate,” she says, eyeing my lemmings.

“They’re not for eating,” I say.

“We’re here to ask questions,” Luxor announces, pulling out his notebook.

“Ah, I already had a team asking questions. I told them everything I know,” she says, but her tone is cheeky. She swivels around and pulls out a lemming from her nest. “You might recognize this one.”

The lemmings chitter among themselves, some high-pitched squeaks, which are either terror or delight, or maybe both.

Mirage turns to me. “He was a colleague.” But she states it as fact, without emotion. I haven’t gotten used to facial expressions yet.

“The agreement, you know,” says the owl.

“Of course,” says Luxor.

I say, “What do you mean, ‘the agreement’? These are my lemmings.”

Orleans looks me square in the eye and damned if he didn’t put his little paw on his hip. “You won’t be eating us. You told us that.”

“Well, I might. I might just get a hankering for lemming in the middle of the night,” I say, with a little jealousy. “Listen,” I turn to the owl, “these are my lemmings, and I’m training them to do things differently. So you can’t eat them. They’re experimental.”

The owl blinks. “Dear, why do you want to change a good system?”

She knows. She knows the lemmings are basically naïve, and that their questions don’t amount to anything. She’s taking advantage of them.

She nestles her wings close. “Feel free to ask me any question you wish—for the agreement,” she adds firmly. She doesn’t look at me.

“Luxor, Orleans. You guys come home. I’ll talk with you.”

They aren’t listening. Luxor has his notebook out, is flipping back through small pages. Orleans holds the inkwell and props it up between the two of them.

Luxor glances back at me to show me how this is done. “Now,” he says, turning to the owl, “about how many lemmings do you eat in a given day?”

“About two,” she says, without pause.

“And how large is your territory?” Luxor asks.

“It is squares forty-five to fifty-three on the loo-tow field.”

Luxor beams, as much as a lemming can. “Well now, that’s a large area. And you only eat two lemmings a day? Do you have a mate?”

“I do,” says the owl.

“And how many lemmings does he eat?”

“He eats two a day as well, on average. Although, lately he has been flying off into other squares.” She turns to her right. “He could be anywhere right now.”

“Exactly,” says Luxor. “And if you had to predict your appetite in

say a year’s time, would you say that you on average would eat the same amount of lemmings?”

The owl thinks, blinking, and then widens her eyes, little explosions of yellow. “Well, I don’t know. Let me see. A year’s time. Why, just thinking of that makes me terribly hungry. You know, anything can happen in a year’s time.”

Without warning, she lunges forward and gobbles up Orleans, slapping her beak against the inkwell. A squirt of red and inky black runs down her feathers. Luxor and the others are entranced. I move forward and grab the owl by her throat and place a hand around her legs, just above the talons—I don’t want to be scraped. I squeeze until the owl’s beak pops open. She must be in shock because she doesn’t try to resist, and I turn her head toward the ground and shake her, trying to make her gag by pressing her throat. Nothing comes out; the owl has swallowed the lemming whole. But I know she can regurgitate. I’ve seen them do it. And with the size of Orleans, there should be a lot more ripping and tearing before she swallows. She’s just trying to make a point.

So am I.

The lemmings are clapping behind me, and I can’t tell if it’s because of what I am doing to save Orleans, or if they are cheering for the “beautiful” death of their colleague.

The wings of the owl slide open like a fan, and she’s big enough that when she flaps, she gets a lot of pull. I stand and she’s flapping against my face and gagging.

“Cough him up,” I say, like a gangster, but nothing is coming out.

The wind bites my face and ears, and I have the owl now shoved down toward her nest, hoping that by gravity something will expel. The wing cradles my face like a palm, reaching around my neck, quivering.

Finally, a body slips out of the owl onto the grass, covered in gunk. It’s actually two bodies, and for a moment I don’t know which lemming is Orleans, but they both appear still.

The Angels of Our Better Beasts

The Angels of Our Better Beasts