- Home

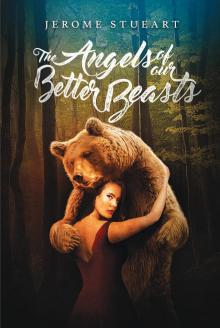

- Jerome Stueart

The Angels of Our Better Beasts Page 6

The Angels of Our Better Beasts Read online

Page 6

“That’s not really our style,” Jimmy says.

“He’s what we got if we want him.”

“How will we know if he can handle Tommy?”

“We don’t.”

“Are we ready to offer him up like Jessica?” I ask.

Jimmy sneers. “There were other complications to that, you remember.”

“We take a chance,” Eric breaks in. “If we’re saying Tommy lives then we’re taking a chance every damn month.” He glances sideways to Tommy. “No offense.”

Tommy nods.

I say, “I’m not letting another stranger alone in the Tinderbox with him. If he dies, we can’t say it’s another wild animal attack.”

“We should hear him anyway,” Eric says. They’re oblivious.

>?

Arno Tomczak is nothing like I expected. First, he has tattoos on his arms: pictures of a man with a green beard, and Celtic symbols, and God knows what else. He has a red beard and one side of his head is shaved, a stripe above his ear. He said his hero was Ashley MacIsaac. He wore sunglasses during the audition.

But, damn, could he play. He not only played our songs but he injected them with fire, rocking back and forth, swinging those dreadlocks as if a creature with a tail. We knew right away we could put him on fiddle solos that would bring down the house.

“Why aren’t you in a bluegrass group somewhere?” Eric asks him.

He rolls his eyes a little. “I’m not exactly the kind of guy you’d find in a gospel bluegrass group.”

“Do you have a faith?” Jimmy asks.

“I believe in the power of music,” he answers, smiling. “That’s all I have.”

You can tell that they’re disappointed. Their pause in judgment makes me like Arno all the more.

“Okay!” Tommy says. “Well, you play like you’re blessed.”

“That’s my mom’s fault. She raised me on the McMasters. When we lived in Cape Breton, I went to as many fiddle camps as I could. Believe me, I was blessed.”

It’s a new sound for us. Undeniably. Celtic rhythms could sneak in anywhere. Could they play with him? Would our fans mind?

“I don’t like the way he looks,” Jimmy tells us when we’re alone. “Not very clean cut.”

“We don’t have a lot of choices,” Eric says. He turns to Tommy. “‘Wondrous Love’?”

Tommy looks like he might weep. That’s when I think it’s all gone.

“It was beautiful.”

The other guys nod. “It was beautiful,” they murmur.

“Was it enough?” and we look at Tommy.

“I don’t know,” he says. He grips our shoulders and we all stand in a circle and weep. “Dear God,” Tommy whispers like someone died. Somehow we know it doesn’t matter—that this is the end. There isn’t enough hope left to fill the room.

We can’t hold Arno out of the room any longer, and we wipe our eyes enough not to look like we’ve been crying. Jimmy says, “He can’t wear the sunglasses, and he needs to cover the tattoos. Just to respect Jesus, you know?”

Eric laughs. “Damn, Jimmy.”

“People are gonna talk,” Jimmy says.

>?

They did talk and it was the end. But it wasn’t Arno’s sunglasses they were concerned with, and it wasn’t the end of the band. The first concert, they introduced Arno carefully, uncertain what their audience would think of his appearance, unable to determine which side they should play—fully supportive or carefully, amusingly skeptical. They seemed to fight laughter when introducing him. They finally settled on a shtick—where Eric and Tommy would be wholly convinced that Arno was amazing, and Jimmy would play the skeptic.

Until Arno played.

His fiddle might as well have been flint and a rock; Eric and Tommy and Jimmy and Wayne were infected with fire, lit from Arno’s fiddle. Every song had a different beat to it now. And when they called for something that hurt, he could crush your heart.

Our booking agent, Kate, started using Arno as part of our marketing, showing clips of our shows. “I’m lovin’ the wild child,” she told Eric on the phone. “And the new sound is great!”

The whole band changed. I heard something new from all of them.

Dear God, they got better. I’d never heard Tinderbox so stompin’ good.

“This is a good sign!” Tommy says backstage one night, high on music and hope. He hugs Arno.

“A good sign?” Arno asks, smiling. Taken aback, maybe.

“We have to record this right away,” Wayne says, slapping Arno on the back. “A live concert.”

Eric says Kate had already suggested it. “She wanted to pick one of our next concerts. I told her Billings was coming up, and she likes Rimrock Auto Arena.”

“Only one problem,” I say. And it’s my job to point this particular problem out. “That’s a short night.”

“That’s a moon night?” Eric asks. “Damn. Well, maybe our luck is changing!”

Everyone gets excited but me. The full moon was a week away, Jessica Hawley is on my mind, and that can sober everyone up.

I push them to take Arno aside. “We can’t wait. He has to know.”

Tommy says, “I don’t want to scare him.”

“He doesn’t look like he’ll scare easily,” I say.

“Yeah, well, he hasn’t seen what’s coming.”

>?

The problem with a killing monster is you have to kill it. I never saw one movie where the monster gets to live. It always dies. And with Tommy, we’d all been stupid enough to believe that he wouldn’t get out, wouldn’t kill again.

No one wanted to spoil the new joy fevering through everything we did. No one wanted to break the spell. I could tell that Tommy was especially hopeful. He’d become fast pals with Arno.

One night, I go into the trailer and take my shotgun out from under the front seat, to get it ready. I pray to God for everything, from health issues to my sister’s relationship, from war in the Middle East to poverty. But I look at this gun and I think cleaning it is a type of prayer. I catch myself saying, “You’re going to shoot straight this time.” I say, “You’re a good gun. You have a heart in you. You don’t want to kill; you want to save. But sometimes saving is killing and killing is saving.”

L’Amour didn’t have bad guys you still liked—they weren’t both good and bad if they needed to die. Everyone was responsible for their own corruption, and L’Amour made sure you knew that they deserved it, that they were blacker on the inside than their hats were on the outside. But Tommy is different, I say to myself, complicating matters.

I’m about to talk myself out of this complication when I hear something above me, and I look up to the ceiling, waiting to hear it again. Music. Speak of the Devil. He sometimes spent time alone in the trailer, even when we were booked into a hotel, just to write music. I decide I would walk up the stairs quietly, not disturb him.

I take the gun.

I can hear him strumming, stopping, writing. I sneak up the stairs.

I’ve not heard this melody before. It was bluegrass, though. You can always tell a bluegrass song: heartbreak, gospel, missed opportunities, hometowns, a fiddle section, a chorus, tight harmonies, and voila—Bluegrass. Not that I don’t enjoy Tinderbox. They’re good, but bluegrass music in general started to feel repetitive after a while. Throw in some Alabama, some 38 Special, Ronnie Milsap, or Eagles, and I can take it. Variety, variety, variety. I like Alison Krauss and Union Station a lot, but maybe that’s because Alison’s voice is sweet as clover honey.

Tommy Burdan is a good songwriter, though. He bends over the guitar, there in the far room, just down the hall from the stairs. From here I have a perfect shot. I raise the gun. Maybe tonight is a good night just to rid us of the problem early—not risk another person.

Tommy strums and sings.

<

br /> In my mind I see him as the beast that had leaped from the trailer door, claws curling, lips snarling, the rage, the moonlight touching the fur of his forehead, his muzzle.

I see him clearly through the shotgun’s sights. I imagine him killing the little boy in Romania, the blood dripping from his monster lips, black rimmed, his muzzle covered in a red so red it was black in the moonlight.

My gun wavers. He continues strumming, and then stops and writes some.

I lower the gun. I have no desire to kill Tommy. I do want to kill the beast. But in this moment, I think—you have to kill him, Tommy. You can’t be two different people—not when one of you is a killer. I can shoot him as a wolf, but I can’t do this here, when he’s singing about redemption, when he can’t see my gun.

I’m going to let him do it. I’m going to give him the keys to the bus and he’s going to drive it off a bridge somewhere, and he’s going to fly through the windshield. He’s going to give the world that one. If we can make up stories about Jessica, we can fabricate one around what happened with the bus.

The night sneaks around like it’s conspiring with us. The wind taps the windows. Maybe it will rain. I nearly get up. Maybe it would make it all believable. Jessica Hawley believed in you. I believed in you. How much good can one person do to make up for a bad? If I shoot you, does God forgive me for Jessica? Does he forgive you? I don’t know how much good can possibly balance that out—how does forgiveness work exactly? What’s the math on it?

You would finally do something good, I think.

Is that what this is? I’m trying to even out my life with this gun.

It sits heavy in my lap.

I know God is really working miracles in this group—how many people we help and all—but can’t he spare one miracle for you, Tommy? Or is that miracle me?

I go downstairs again, put my gun under the seat. I hear Tommy come down behind me.

“Oh, I didn’t know anyone was here,” he says.

“Just checking on things,” I say.

“Hey, Arno’s really working out, isn’t he?”

“Have you told him? What he has to do?”

“Not yet. I don’t want to force it.”

I look through the front windshield of the bus at the moon. “That moon’s going to force it if you don’t.”

>?

So, Tommy sets it up. We sit one night in the tour bus, in the tiny living room with the fixed tables and the striped cushions. The night grows crickets, and a breeze comes through the screens—we’re somewhere in Missouri. Shastas all around, any kind you want. We’ve just finished some of Eric’s chili. We’re all tense, and trying to disguise it with laughter. Tommy sits across from Arno, strumming on his banjo.

“We need to talk to you,” Jimmy says to Arno.

Poor man. He looks at all of us, rubbing his hand across his face.

“I knew it. I knew you’d find out. I want to say my peace before you say anything.”

“Arno—”

“No, I get to talk first,” he says. “Yes, I’m gay, and yes, I have a boyfriend. And I may not be a Christian, but I’d like to at least like Christians, but that’s been hard because this business—bluegrass—is filled with them. You guys may be the most Christian of the whole industry, but for the most part, bluegrass musicians are Christian, usually pretty conservative, too, and that’s not been easy if I want to play at festivals. I don’t mind people looking at my tats, my hair, my piercings—I don’t care. All I care about is music, playing music, because Christian or not, you have to admit there’s a spirit there, in music that lifts you, and I get that. I want to have it just like everyone else. I want to play with other bands, and I don’t want them to make an issue about it. I’ve been in two bands. I won’t name names—okay, The Weilands and Prairie Storm Players—and they dropped me like I bit them, and I won’t go through that again. I’m not going to fight you in public, but I’m not going to just slink back into the night because you’re uncomfortable or you want me to change. It’s not going to happen.”

You could have heard salt spill.

Eric looks at Jimmy. Jimmy looks at Tommy and back to Wayne. Then Jimmy looks at me.

Tommy says, “I think we’re okay with you being—gay.”

“Well—” Jimmy starts, clearing his throat for what might have been an epic speech.

Tommy interrupts. “Even Jimmy is okay with that. Because we need you.”

“So you didn’t call me in here to drop me from the group?” Arno asks.

“No,” says Tommy.

“Oh, I’m sorry, guys.” Arno laughs. “That’s cool. I’m cool. I’m sorry. Wow. That’s so good to know. I think I’m gonna tear up. I didn’t know what you’d say when you found out. This is better than I thought. So much better. It’s been a long haul in this business, you know. I forget sometimes. It just looked like you called me in here to tell me bad news, you know?”

We got quiet.

“You have bad news,” Arno says, tentatively.

“Well, that depends on you,” Tommy says.

“On me?”

“Arno, I need to tell you something you can’t tell another living soul. Can you swear to secrecy?”

“Sure,” Arno whispers. “I mean I figure you’ll keep my secret. What’s yours?”

Tommy says, “I want to tell you a story about my time in Romania.” And he does. The whole story, only looking up a couple of times.

“I want to tell you about the people who have died.”

Arno looks at each of us, to see if we believe.

“I want to tell you how you can keep that from happening ever again.”

Tommy lays it out. About “Wondrous Love.” About how many times, how long he had to play it, and what it would do for Tommy.

“This time,” he says, “this time Carl is going to be in the room with us and he’s going to have his gun pointed at the door, and if I get out of that room, he will shoot me. Because a monster is going to come out of that door. It won’t be me. It’ll be something that will kill you.”

Tommy stops talking. “Can you do it?” he asks Arno.

I don’t think Arno had breathed for about ten minutes. When he does, it comes out in a rush. “What the ever-loving fuck are you talking about?” he says. “Pardon me, Jesus. But that’s about the most fucked up thing I’ve ever heard. I thought you’d freak out at me coming out, but are you playing a joke on me? Is this what you do to people who really tell a secret?”

“No joke.”

“You gotta watch that mouth,” Jimmy says. “For the Lord’s sake and all.”

“He just said he was a fucking werewolf,” says Arno. “Did you hear that?”

No one moves.

“You all think he’s a werewolf?”

We all say yes—our little confessional in the kitchen.

“We’ve seen it,” Eric adds.

Arno breathes out. He looks worried, like he’s on the edge of something frightening. I sympathize. “None of you are bad people,” he says. He picks up his Shasta. “You have a fucked-up problem. Okay, I get it.” He slurps from his drink, eyeing us. “If Jesus was a zombie and needed to eat brains, would you still do what he told you? Would he still be a good man? That’s where we are. In twisted Bible-land.”

Jimmy shakes his head. “That is not what we are saying.”

Arno looks at Tommy. “You’re a werewolf?”

Tommy nods.

“Okay,” Arno says. “And the werewolf has killed two people?”

Tommy nods again, his eyes watering. “I don’t even remember it.”

“And you’ve told no one this?”

“Who would believe us? They have to actually see Tommy change,” Jimmy says.

“The only thing anyone could do is kill Tommy,” Eric says, breaking down. “Exce

pt for that one song. Amelia kept him good for the last ten years, God bless her. Was a miracle every time it happened.”

Jimmy soon joined the chorus of crying—all of us desperate men now, asking for a miracle from someone we just met.

Tommy has pushed his face into the blinds, his eyes shut, crying. Arno reaches across the table and puts his hand on Tommy’s arm. “Okay.”

“We’re concerned about you, Arno,” Eric says. “We don’t mean to put all of this on you. We shouldn’t have put it on Amelia, but no one had a choice. Who knew it would be that one song?”

For a moment, with Arno touching Tommy’s arm, and all of us looking at Arno, wondering if he would accept us or not—if he would think we were killers because we’d kept this secret—or if he would want to leave the group before the next full moon, we wait to see what he will do.

Arno finally looks at Eric. “I just have to be good,” he says, his face trying to smile. “You need someone to be a little musical Jesus right now and save you guys. I don’t know if I can do that, but I’ll try. I’ll give it a shot.”

>?

Tommy disappears the next night. We’re in Billings, Montana for a show. We did the sound checks in the afternoon, went to dinner, and, afterwards, Tommy said he was coming back to the bus. We searched the hotel, the trailer. I ran up to the top deck, opened the curtains to all the bunks; checked the bathroom, the Box, everywhere. I feared he was going after Aaron, going to beg Amelia to come back, as if she would.

I call Amelia to let her know. She’s concerned. “He doesn’t know where we are,” she says quietly. “I’m not going to tell him.”

I tell her I understand.

“I’m not trying to be heartless, Carl. But—” and she goes silent; all I can hear on the other end is her breath, and a radio in the background—country music, something bright, something happy. “Carl, I’m pregnant. I was pregnant when I left. I want a family. I don’t have the strength to play,” she says. “To save him.”

“Pregnant?” My worst fears are realized. “I’ll kill Tommy.”

“It’s not Tommy’s. He never touched me. He never tried. He never wanted—” she stops. “If he comes here, Aaron will probably kill him or turn him in with what he knows. You can’t let him come here, Carl.”

The Angels of Our Better Beasts

The Angels of Our Better Beasts