- Home

- Jerome Stueart

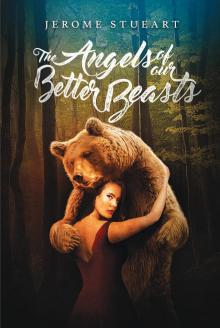

The Angels of Our Better Beasts Page 4

The Angels of Our Better Beasts Read online

Page 4

And saving all our asses when the moon was full.

If church groups knew what Tommy Burdan turned into on moonlit nights . . . what he tries to do—what he’s done. It’s our little secret. All of us, sworn to keep that secret. “Because the good we do in the world far outweighs the danger,” Tommy says. “No one has to know. We keep it—we keep me—shackled in the Tinderbox and we don’t have a problem at all. We lock up the devil. The devil won’t destroy the good we’re doing. We won’t let him.”

As long as we all agreed to never tell. That almost always worked.

But beautiful Amelia had to take the brunt of keeping us safe. She was the one to put up with it, to have to work extra hard to contain him; it was her that walked out of the shaking tour bus at night, and sometimes they looked at her differently, as if perhaps she didn’t just play the fiddle to calm him—that maybe she did something else.

The only song that could contain him was “Wondrous Love,” normally a four-part harmony sung by the guys, with Amelia’s fiddle. But even if they could have sung it without Tommy, he wouldn’t accept anything those nights but Amelia on the fiddle. So she, by herself, played that tune hours and hours on end, until the chords and the notes buried themselves in grooves on her face.

Tommy never remembered anything.

It was my job to go unlock the Box and take Tommy out.

We don’t usually have much to say to each other, because I’m a bus driver, and, well, after someone sees you like this, it gets awkward.

I swear to you, it reminds me of my rehab days. I used to be an alcoholic—wait, I am an alcoholic; you don’t stop being one because you stop drinking. I was the kind of man who couldn’t remember 50 percent of his time on Earth because he drank it away. I’d wake up, much like Tommy, with no recollection of the night before, with rips in my clothes, lost wallet, smelling like booze and sweat and barf. And I called that living for more than twenty-five years.

Tommy is passed out in the chair, his arms bruised and skin broken open again, the shackles having ripped into his flesh from fighting. Not as bad as if we didn’t have Amelia, but still not pretty. Takes him a week to heal up. He’ll wear a white arm brace and roll the sleeves of his white shirts down to sign autographs. His fans never know what his arms look like; they can’t see him like this, or like he is on those nights when Tommy is lost.

His head lolls back and the sunshine hits like forgiveness.

Unstrapping him, I think, good for him—he gets all that money and all that fame and all that love and all that grace because no one knows he’s a monster. I admitted to myself and others that I was an alcoholic and I sought treatment, and just telling people that makes them judge me. I don’t get treated as well as Tommy does here. Alcoholics are messed up sinners—and werewolves? Why, play a good banjo, talk about Jesus, and you’ll have them in the palm of your furry hand.

>?

“You can’t do this to yourself anymore, Miss Amelia,” I chide after I’ve put Tommy to bed, and I know what I’m doing. I know what I’m saying may make a difference.

Amelia runs her eyes over my face. We’re beyond arguing this morning; she isn’t playing along with my chatter. I can see a tear in her eye as if this time, this time, she believes me.

“It’s not good for your heart,” I say. The wind tries to catch my hat from my head.

“How do we know what’s good for our hearts?” She looks over the plains of this strip-malled small town, and I know she’s in more pain than I can bear to see. She needs someone. To find a new man—someone who could really love her. Pretty single girl like her, she could have her pick.

“If I don’t stay,” she says, looking at me with eyes I fall for every morning and every night, “we don’t have a group anymore.”

“You can’t let him trap you,” I say. “You have a life—maybe far away from here.” I say this a lot, but today, I’m making it count. I’m going to nudge her away, because without her, it will all come to a head. And then we’ll have to do what we need to do.

I know she’s been approached by other record companies, other labels, a fiddler of her calibre. You have to hear her. Yes, she charms werewolves, but do you know what that sounds like? She can charm thousands of people at a concert, too, entire rooms freezing in place, listening.

She turns away from me, stares across the horizon at Texas trying to look busy on the highway beyond. She sighs. Her red hair falls off her shoulder.

“A life is okay to give away, isn’t it? So that other people don’t die?” she asks. “It’s what God asks of me, right? It’s the right thing to do, right?”

“It’s not the right thing to do if it’s killing you,” I say, pouring her some coffee. “God isn’t into making you kill yourself to keep someone else from killing.”

“How do you know that?”

“Ask my ex-wife.” I smile, trying not to reveal how much it all still hurts.

She nods, the kind of nod that tells me this time she’s thinking hard about leaving.

It’s me you should blame for pushing this to a showdown between a werewolf and God himself. Not her. It was her decision to leave, but I just asked her to honour that decision. That day, the morning sun played tricks with her face, making me think a person’s doing better than they are. Little did we know that she’d already met someone, and that this was also tearing her apart.

>?

Tommy lives by the numbers. In the kitchen in the trailer, there is a whiteboard with the number 2 on the left side, and the number 11,324 on the right. The number on the right is the number of decisions that have been made for Christ at our concerts: lives turned around by the power of Jesus, but also literally by the music of Tinderbox—things Tommy Burdan felt he had control of. Each song he wrote, each time he played, he put everything he had into it, as if the words themselves, the tunes, could turn a heart, save a life.

The number on the left, those are the deaths. The people Tommy has killed.

“The people the monster inside of him killed,” Jimmy reminds me. “Not Tommy.”

It’s what we say to ourselves. That there’s a monster; that Tommy is not responsible. Do you know what that sounds like to me? That they can split Tommy into a monster and a good man, like two different people. I want to believe that, too. But I had a wife and a kid once, before I became their bus driver. Like another life, another Carl. And they blamed me. They didn’t split me in two, and I have a hard time splitting Tommy in two—and blaming something we can’t see.

I’ve heard it, though. Heard it growl inside the trailer, through the strains of “Wondrous Love” I heard it growl—that thing—and I want to give him the benefit of the doubt.

I once filmed it. No one knows, but I hid my camera in there, just beneath the small table, and I caught the whole thing on film. I had to watch it. I had to watch what he became so I could understand. His face stretched, his muzzle came out of his face, his lips tore back revealing teeth and fangs; his body got larger, the shackles strained, but the music, the music seemed to keep him from struggling so much. But I saw him, completely wolf. I saw it. I knew what he became. I watch that video sometimes when I want to remember what we have on our hands. What Amelia deals with.

Some days Tommy stares at those numbers, just stands there and believes, believes with all his contrite, banjo-playing heart that him staying alive and playing is penance enough for the two lives he’s taken. That some mysterious number—10,000 or 12,000, or a million, will equal the loss of two.

Nothing can replace two lives. I know.

>?

God knows it was nice seeing Amelia laugh again. I was proud of her—happy for her. When Aaron started showing up at all the concerts, a good ole boy from Omaha, with a black hat that he’d remove only when Amelia was playing, well, I knew she wasn’t long for the road. And heavens, she’d been with us for ten years, and not really

had much of a life. In our off-season, she’d follow Tommy home to keep him under control; his was a year-round illness, and she felt obligated.

Tommy treated Aaron with cold, unspoken contempt. When he wasn’t busy, he would try to corner Amelia. I could overhear them—not his words, but his tone, pleading. Once he said, “You know what this means?” He never really loved Amelia; he needed her. I always thought of her as a drug for him, for the part that turned into an animal.

I confided to Eric while we were washing our hands after a long practice and sound check that Tommy just needed to let her go.

“He’s never going to do that,” he said over the sound of the water.

“Holding her captive,” I grunted. “No one’s gonna say that though. Because we don’t want to say what needs to be said.”

“Yeah, well it’s her decision.”

I dried my hands. “Are you sure?” I said, looking at his face in the mirror. I tossed the paper towel into the basket and left him there.

At the concert, when Aaron showed up backstage and pulled Amelia off to the side, I made sure Tommy saw it, and then pretended to hold him back. “You don’t want none of that.”

Eric plucked at his Dobro, glanced up at a seething Tommy. “You know, it’s hard for me to say this, or for all of us to admit it, but it’s time to let her go.” I knew Eric. He liked to do that. It was on his mind, so it was out his mouth. He just needed someone to put it on his mind.

“I get it,” Tommy said. “No one has to spell it out.”

But after the concert—a double encore full of prayer and praise—backstage after the crowds had left, Tommy nearly punched Aaron.

“Bad things will happen if she leaves,” Tommy told Aaron, walking into him.

“I know,” was all Aaron had to say. What he meant was that he was aware. Aaron just stared at Tommy, eyes never blinking. And then he winked. Tommy leapt on top of the man, and Aaron threw him to the ground. Aaron had to be 250 pounds; he held Tommy down on the ground, and I could hear him say, even as we tried to pull him off, “You let me know if you want someone to knock the shit out of you on those nights. Maybe that’s what you really need.”

Tommy threw a punch, but it missed.

“I’m gonna take her,” Aaron said.

We pulled him off, but not before it got worse.

“You won’t be able to find her,” he added.

After that, Tommy banned Aaron from their concerts, hoping that would keep him away.

Instead, it upset Amelia.

She stayed with us for one more full moon, and then disappeared the next night, completely. All her stuff removed from the bus. Only a short note, a ragged piece of paper towel, ripped off in a hurry, to tell us that she’d gone.

I’m sorry. I can’t do this anymore.

>?

I saved one. It’s a different feeling when you do it out of goodness than when it’s because you’re a bastard. When my wife and daughter left, they were escaping me, and what I could do to them. They scared me back into myself.

Amelia just scared us.

It hit them hard. Tommy was crying, praying, begging God to bring her back; Wayne was making the necessary calls to Kate, the booking agent, to the team back in Nashville. Jimmy looked completely bewildered.

“This is the end. This is the End Times,” he said.

Eric sat with him at the little kitchen table on board the bus, as if someone had died.

We were outside Evansville, Indiana. The sun was bright. Cars passed on the distant bridge, oblivious; no one here knew what could happen. We had a break before our next string of shows. At least we had that.

“She knew she was the only one who had to stay,” Jimmy said. He cupped a Shasta Black Cherry soda in his hand.

I said, “Everyone doesn’t have to stay.”

“We’re all in this,” Eric said. “We all have to do the magic now.”

“What’s gonna happen to the group?” Jimmy asked.

Someone’s gonna die, I thought.

We were on a ticking time bomb. We had twenty-eight days after she played her last “Wondrous Love” in the bus. Twenty-eight days to figure out how to contain the monster inside Tommy Burdan.

>?

So here’s the kind of meeting that five bluegrass players are forced to have around one of those pull-out tables on a tour bus.

“We can reinforce the Box,” Wayne says. He talks with his hands, as if building it in front of us. “We can afford a stronger door, a chair with bigger cuffs, all metal. I bet we could get one in place.”

“How’re the installers supposed to catch us while we’re on tour?”

“I can do it all—well, when I’m not playing bass.”

Wayne is a great carpenter, but his welding is sketchy.

Drugs are no good. Getting him drunk is no good. Only Amelia had seen it full, through the window of the Tinderbox. She’d seen him change—none of us were brave enough. When he turned, the music was all that stopped him from ripping down the whole bus.

“We could play a tape and cover the window so he doesn’t know that she’s not out there.”

“I still have my memory,” Tommy says. “I know she’s not going to be out there.”

“Tommy, I think we need to have a conversation with just the rest of us for a bit. I don’t mean no offense, but we need to talk about our commitment to this group, and what this is all gonna mean for us.”

Tommy stands and rolls up his sleeves, showing the scars on his arms. They ripple across his flesh like lumpy white rivers, and he shows them to us, slowly. “No offense, but this means a lot more for me than it does for you. I’m gonna stay.” He looks around at us, and no one speaks. Eric adjusts his hat. Tommy continues, leaning in, “We haven’t tried electrocution, a continuous tazer.”

“Tommy,” Jimmy says, “who knows what that will do to you.”

“We already tazed you before. It just makes you mad.” Eric corrects himself: “It mad, I mean.”

“You just taze me until I’m unconscious—hook it up through the metal shackles.”

Wayne looks around. “I don’t know how to build one of those—whatever it would take. That sounds pretty industrial.”

“What if we take out your teeth?”

“And nails?” Tommy says. “We don’t know if I’ll just regrow them.”

We all look worried. I’ve never heard us so desperate.

We sit there silent for a moment, so long it felt like a very sad prayer session.

“Well,” Tommy sighs. “That’s it. I’m calling it.”

The other guys stand up; I stay seated. I want to see what happens. Call me curious, but I’m not sure that Tommy would ever take his own life. To do that meant he would end the ministry, the numbers board, the little game he played with himself about whether he’d made up for the dead.

“No,” Jimmy says, grabbing Tommy’s arm. “No one’s ending it like this. We have twenty-eight days. We’ll come up with a solution. You’ve been this for ten years. You’ve lived with this, and we’ve lived with this, and we’ve made it through.”

“I’m not going to shoot you,” Eric says.

“I’m not going to either,” Wayne adds.

I don’t say anything.

Either we had the group and we were making music that praised God, keeping that monster subdued, or Tommy was on his own and a killer, or he was dead. These are the only three choices we had, and no one here could kill Tommy in cold blood.

“The good that we are doing in the world,” Jimmy says. “We—I . . . I can’t believe God is just going to leave us like this.”

I seriously wonder about a god that would let Tommy live. But if I can believe that black dog was the devil, then I can believe in a god that’s come up with a way to contain all that werewolf.

E

ric wipes his eyes. “We haveta pray harder. I don’t understand why there’s not a miracle for you. I don’t understand it. I don’t understand why someone who is doing good doesn’t get cured. Or when someone dies of cancer who was doing good stuff in the world. I don’t understand. Is it us? Have we not prayed enough? Am I—am I doing something wrong?”

Tommy hugs him. Jimmy hugs Tommy hugging Eric. Wayne just places a hand on Jimmy’s back.

I hear Tommy say from within the bundle, “No one’s doing nothing wrong.”

We could have you arrested, I thought. We could ask them to put you in solitary confinement for one night. What would that do? They pray out loud for a miracle to happen. It’s not like they hadn’t done this before. In some ways, maybe Amelia was the answer to their prayers for so long—our little method of hiding him, or taming him.

I think about my 12-gauge under the front seat, about shooting him and saving everyone—and that he’d thank me in heaven, probably. We could report in the newsletter that he’d gone back to mission work, or that he got hit by a bus and make him a martyr. If we could keep his secret in life, we could keep a secret about how he died.

When it’s a killer you become, a raging, child-killing, adult-killing monster—and the charms are all used up—there’s only so much praying you can do. Surely if God could have cured him, He would have.

“I will shoot you,” I say, a little frightened of my own voice.

The prayer party erupts, bluegrass players everywhere. “Carl!”

“Good God, man! Who put you in charge of that?” Jimmy says.

I stand up. “Someone has to do it if it needs to be done.”

“I can see you as a killer,” Eric says. “I could always see that.”

I figure my soul is sullied already. “No need to dirty your souls, boys.”

Tommy comes over and puts a hand on my shoulder, his eyes sincere, even gentle. I confess in that moment I’m not sure I want to kill him.

“I appreciate knowing you’ll do that for me,” Tommy says. “I’m so glad you said that.”

The others don’t look so sure. I’ve never been loved here, I can tell you that. But I can also tell you that the looks I get from the group chill me, as if there are monsters inside them, too.

The Angels of Our Better Beasts

The Angels of Our Better Beasts